57. CONNOR DILLMAN: A SPACE BETWEEN THRESHOLDS.

Connor Dillman,‘You are here’, 2024, 31.5x23.5 inches, oil on canvas.

‘Los Angeles…the city’s underbelly can be intoxicating. I would try to articulate it, but Bret Easton Ellis’s Less Than Zero does it best. I remember getting chills the first time I read one scene in particular in that story where Clay, the narrator, sits in drugged malaise at a Hollywood restaurant, watching as his ex-girlfriend’s car “glides out of the parking lot and becomes lost in the haze of traffic on Sunset.” My adolescence was spent reveling in that mundane, sun-baked magic. It fuels some people and swallows others.’ C.D.

Your work really fascinates me because I see a certain stillness within it, and yet there is also a feeling of movement, which feels sort of televised - as if the screen is frozen and these fragments are part of a larger frame... something entertaining and yet there is always a feeling of serenity which sort of breaks the context…

I appreciate that observation. I think the mood you’re describing is a result of the way my brain solidifies the visual information I absorb. Similar to how a writer might revise a first draft many times to sharpen its original form, there’s a kind of spontaneous honing process that happens once I’ve identified the skeleton of an image I need to paint.

Say for example that it comes from an in-situ sketch or a memory—there are blurry fragments of context attached to those kinds of source material. Working with that liminal recall can be exciting, but right now I’m more interested in what happens during the making of a painting when context is allowed to fall away in favor of a refined image with a certain cryptic conviction. Or hieroglyphic sensibility. And because these pictures often contain human bodies paused in poses, they can definitely nod to filmic compositions.

I remember walking through the studios in white city and seeing you working - engrossed within your internal space - can you reflect upon the space that you enter when you work?

Recently I’ve been thinking about my time in the studio as a series of thresholds. On the best days, where there is nothing to do but paint, it’s like slowly sinking through the zones of the ocean. Warming up physically is one threshold, trying to clear my mind is another. Then sustaining unbroken focus for a bit can lead to a nice flow. But a level beyond that is when I’ve been working steadily for a couple hours and the needle suddenly drops into a groove of blissful play bordered by deep concentration. That’s a sacred space for me. It’s where time doesn’t matter and my intellectual curiosities meet my childhood propensities. The ultimate mirror.

Connor Dillman, Los Angeles, 2022.

I remember you talking about being from Los Angeles and saying how the flashy side that maybe we know from Hollywood doesn't resonate with you as much as the nature side - do you still feel this way?

It’s true that my favorite spot facing the Pacific near Tower 21 on the Santa Monica sand will forever be where my soul meditates. It’s also true that I felt pretty out of sync with LA’s culture when I worked across a few different areas of its entertainment industry after college. In retrospect, though, I realize the tension I was carrying then had as much to do with my own lack of creative fulfillment as it did with that world’s frantic pace and overwhelming pressure.

And even the city’s underbelly can be intoxicating. I would try to articulate it, but Bret Easton Ellis’s Less Than Zero does it best. I remember getting chills the first time I read one scene in particular in that story where Clay, the narrator, sits in drugged malaise at a Hollywood restaurant, watching as his ex-girlfriend’s car “glides out of the parking lot and becomes lost in the haze of traffic on Sunset.” My adolescence was spent reveling in that mundane, sun-baked magic. It fuels some people and swallows others.

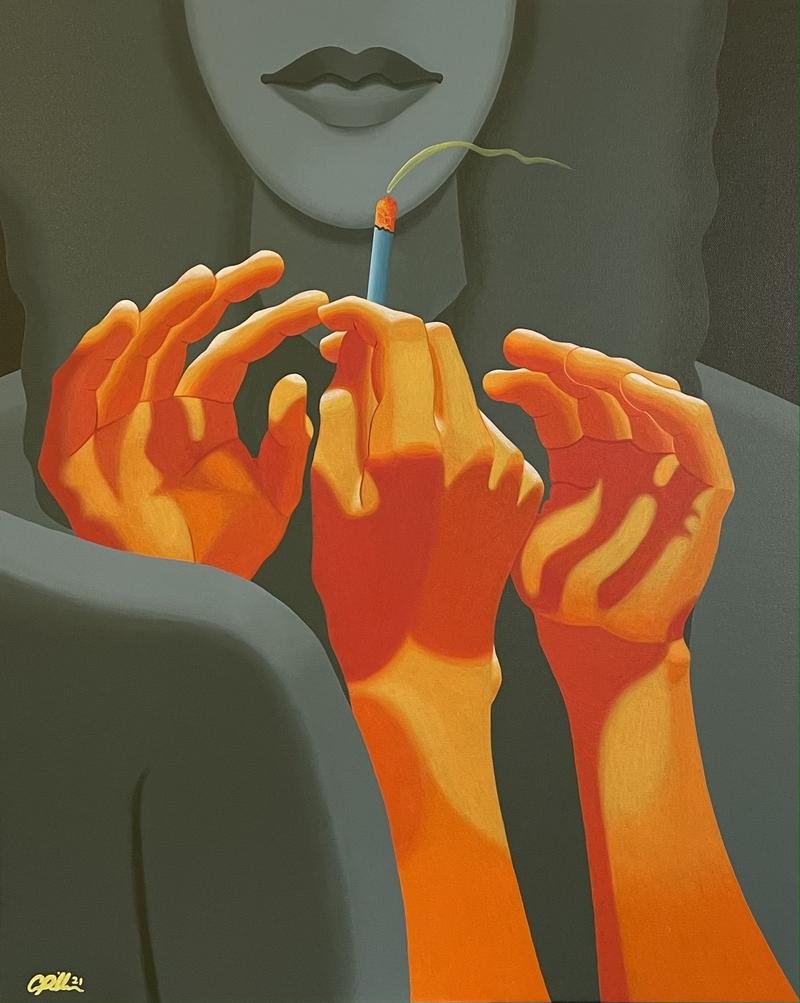

Connor Dillman, ‘E 16th St’, 2021, 24x30 inches, acrylic on canvas.

Your paintings seem to often be self-portraits, can you express why this is and what it is you have learned about yourself through the act of depicting yourself through your work?

Paintings can’t lie about the mental state of their creators when you stand in front of them. I’ve had many conversations with artist friends about that phenomenon of someone looking at a painting you’ve made and then naming a feeling they get from it that touches on something specific that you were contemplating privately while making the work. There’s a 1655 Rembrandt self-portrait hanging in the National Gallery in Edinburgh that paralyzed me when I saw it last year; the dire circumstances surrounding its creation came as no surprise when I learned about them later.

The primary function of self-portraiture for me is related to this transmission. It’s certainly cathartic to ruminate on life in real time when I paint myself, but more valuable to me is the experience of coming back to a self-portrait after a significant amount of time has passed since completing it. Its emotional truth then becomes strikingly clear and gives me a potent zap of the energy I was emitting at the time I made it. For me, there’s really no other mode of self-examination that compares.

You have lived in London for a few years now, why did you want to be here? And what has London taught you so far?

My conception of home is complicated by the fact I’ve always felt more of the world than from a specific part of it. I was lucky to grow up in a family that consistently traveled outside of America, and I think that’s a main reason why I felt tugged towards a place where I would be surrounded by people whose cultural backgrounds differ from my own. There are days walking in the busier parts of London when I’ll hear ten different languages being spoken in the span of five minutes—it’s a constant reminder of the scale of the human procession we’re a part

of, which is invaluable for coloring my life and practice with a sense of urgent purpose on a daily basis.

And on a less existential yet equally important note, my community here reflects this international diversity, which has completely changed the way I approach my relationships. It’s a privilege and so edifying to be regularly exposed to unfamiliar angles on language, friendship, politics, food, love, music…the list refreshes itself with each new day here.

Connor Dillman, Big Bear Lake, 2019.