55. BENJAMIN JONES - A SPACE BETWEEN TOUCH AND TIME.

Benjamin Jones, Binder #39, Binder #40, both 2023. Courtesy the Artist and Loom Gallery, Milan.

The first piece of work I ever saw of yours was a large print of a map made on carbon paper, where each place name had been crossed out - leaving a document of erasure -

It feels a long time ago now, but certainly still has echos in the current work. At the time I was thinking about how meticulous the process of mapping landscape is, compartmentalising and revealing through language and visual data. I was looking particularly at the UK National Parks which have this aura of being more natural / untouched / wild spaces, though of course are heavily human-altered landscapes. It is also a process that compresses history into a single plane of information.

I took maps of the Parks and crossed out every place name. Erasure provided a way to work against a sense of knowing a place via this overlay of information. To have this data is a comfort, promising predictability when navigating; the land has been charted, there are no unknowns. So this erasure is asking how our sense of place is shaped by information, how we project it onto reality, how this sense of knowing a place through it perhaps allows us to ‘confuse the map with the territory’, to believe that the totality of a place can be known in abstraction.

There’s also a reference to the past and future of these landscapes; in that they suggest a time before language had compartmentalised space into places, but also a future point where this language is somehow unreadable to whoever may be viewing it. This aspect of being able to simultaneously read multiple time scales or points of reference in a piece is something that I’ve remained interested in, and that carries through much of my work since these maps.

Benjamin Jones, Untitled (National Parks), 2016. Courtesy the Artist. Image: John Taylor.

There is a reoccurring sense of physical space within your works, of land masses and of tangible surfaces that seem either to be very close or very far away - do you feel this and if so why is this?

There are varying scales of time present across the works, most often signified through natural subjects or the traces of darkroom processes. A work such a View Towards the Pacific 2019-22 deals with the geological timescale of erosion; the poppies published in issue #3 M-A (A SPACE BETWEEN) in contrast are far more ephemeral. As viewers, the span of our own lives are in a kind of dialogue with these various rhythms and cycles in the natural world.

Benjamin Jones, Morning, Afternoon #2, 2023. Courtesy the Artist and Loom Gallery, Milan.

The work Morning, Afternoon, a photograph of the sky with two suns published in issue #3, provides another example. A group of these works, printed on dibond panels, were installed throughout the village of Pieve Tesino, in Trentino, Italy, during summer 2023. They were made in response to the story of the village's shepherds who in the 1600’s left shepherding behind to become print sellers for a local print-works. They travelled the mountains on foot, going as far as Moscow and South America, away for great stretches of time. Their wives and children remained at home in the village; the two suns became a way to relate to that experience of separation via the measuring of the passage of days, tracked by the suns progress across the sky. Of course at this time, communication across such distances was nigh-on impossible for the average person. So these works use landscape to relate historical experience to the present. They were installed floating slightly off rough stone walls in passages, stairways and alleys, to generate chance encounters when navigating the village.

Installation view of To Live Inside a Second, Pieve Tesino, 2023. Produced for Una Boccata d'Arte 2023: a project by Fondazione Elpis in collaboration with Galleria Continua and the participation of Threes.

When I think of your works published in issue 1 and 3 of M-A (A SPACE BETWEEN), I think of first impressions and then as the eye settles into the image, the picture seems to change, emerging into something else, is there a process you tend to follow in the production of your works?

I’ve always been interested in how process and materiality develop meaning. Whether this is Giuseppe Penone cutting back the layers of a trees growth or Liz Deschenes photograms that integrate a viewers reflection and position into the work. It’s for this reason that I primarily use analogue processes; materials that are sensitive to light, touch, time, chemistry, exposure. Photography enables the image to be effected by and in dialogue with these aspects. Experimentation with process, exploring that particular language, is a constant in my practice. One that has resulted in various abstract groups of work made in cycles.

I also make ‘straight’ photographs, that are sometimes printed immediately, sometimes wait in the archive for a few years, and often are re-printed with different exposures, scale and paper type at different times; so a long term relationship with these relatively few selected images. What is significant for me is their poetic capacity for meaning, for engaging with the viewers interpretations, emotions and speculations, eschewing reliance on fact and narrative in favour of emotive weight. It’s due to that constant sense of more to be discovered that I return to poets such as Philip Larkin, Wallace Stevens and Leontia Flynn for example.

Thinking back to the works published in issue #1, a number were from a group titled Binder. These are collages I've been making since around 2019, with a new cycle of 7 completed last year. They are created by projecting multiple negatives onto sheets of light sensitive paper in the darkroom, masking different areas during each exposure to print each image into different areas, sometimes overlapping (and going black), sometimes remaining blank. They fragment the botanical source images and weave them together, pushing back at recognisability, setting these organic forms within a geometric framework. There is a lot of chance involved, the process layered enough that I can't exactly prefigure the outcome. This is one process of many, and a large part of what I do is experimentation with the materials to develop such approaches that define a group of works. Another example would be the group Fog, made with light, chemistry and light sensitive paper. Whilst Binder fragments and collages photographs, Fog appears somewhere between appearance and disappearance, with no discernible ‘image’. The title refers to the 'fogging' of paper; an accidental exposure to light. Defining the parameters before introducing chance is centrally important; the opposite is true in printing the straight photographs however, which require a lot of precision.

Across all these groups, I’m interested in what the experience of that final photographic object is. There are therefore commonalities, with most works made using a specific heavy weight, matte silver gelatin paper, displayed without being mounted to a substrate and so retaining a more sculptural form. Their frames are specifically designed to emphasise this object-hood, the sense of the print as a unique object that through material and scale has it's own history and presence. Bound to it's referent but independent, not a ‘window’. With emphasis on how it establishes distance from it and generates potential for new meaning, that as you recognised, has the capacity to change with time but also with the viewer.

Benjamin Jones, Poppy, Provence (4.1), 2023. Courtesy the Artist and Loom Gallery, Milan. M-A (A SPACE BETWEEN) issue 3, 2024.

Your meadow series have such a sense of calm, they are fragile and strong, fleeting and yet have a permanence - and needed to sit as a set to conclude the new issue of M-A. Please can you expand as to the process of how this series came into being and what they mean to you?

That fragility you picked up on is really at the core of it. When photographing something so small so close up, the physics of the lens dictate an incredibly shallow focus, itself something slight, delicate. These pictures are a kind of balancing act, a fragile slither of clarity prescribed by the proximity of camera to subject. I’ve never been so interested in making photographs that propose a neutrality or objectivity. The subjectivity of photography, its apparatus and materials, and the way it re-presents the world to distill or suggest something other, is what I’m interested to explore. So making these pictures became about this act of looking closer, taking a perspective less defined by our own bodies; so being on the ground, focused at this close distance, and making monochromatic images of these multicoloured scenes.

The whole series was made within a ø10m circle in an olive grove in Provence, where I was on a residency last year as part of the Galerie Heimet/NG Art Creative Prize. Traditionally the ground between trees is cleared to minimise competition for nutrients. In this case it hadn’t been, with great botanical biodiversity the result; that also provided a habitat and food source for numerous insects. I became interested in this overlapping, tangled world hidden nearest the ground, like looking at the weave that comprises the wider landscape. A less ordered space, more chaotic and opposed to agriculturally organised space. They are structured photographs, heavily composed and pictorial, something that emphasises their constructed nature as a trace of their subject. Their relationship between ephemerality and permanence then, is centred on the fact of these plants brief existence and the way their appearance punctuates the seasonal cycle; participating in processes of pollination etc, that are part of a slower, deeper natural rhythm.

You have a particular relationship with Italy which seems to be evolving, can you expand upon this connection and what you have learned since being based there?

Since 2020 I’ve been working with Loom Gallery in Milan, and so have produced a number of projects with them including a solo show in the gallery last year; previously a collaboration with Antonini Milano and group presentation in Ljubljana. The conversations around the work have been brilliant, and so of course you meet people, the work is seen, new collaborations are instigated; there’s a fantastic energy there. The most significant of these was an invitation last year to participate in Una Boccata d’Arte, a nationwide project initiated by Fondazione Elpis and Galleria Continua, that included a residency and public commission in the village of Pieve Tesino, Trentino. It bore the Morning, Afternoon works I mentioned earlier, and a large piece (To Live Inside a Second) that will become a permanent installation. The whole project was developed in response to local histories and installed throughout the village during summer 2023. So indeed the relationship is evolving, with opportunities to expand the scope of my practice through these sorts of collaborations.

What has been learned specifically is somehow difficult to pin down; of course it’s bound up in personal and working relationships, exposure to different histories and places. It's really a sedimentation of all the conversations, interpretations and opportunities to develop the work. It is also however the increased awareness of Italian art, design, landscape and architectural history; experienced in a way that research from afar does not permit, understanding the shape this history gives to the present, and how it underscores a sensibility.

Since the pandemic years life has changed near unrecognisably, and so it's hard to separate everything out. The experience has regardless been formative, and I now travel there multiple times a year. It’s become a hugely important place, now populated with great friends and collaborators. The opportunity to work intensively in any country other than your own I think gives a stronger sense of the changing world, of commonalities and localised challenges, and a new perspective on what defines the culture you originate from.

All works courtesy the Artist and Loom Gallery, Milan.

All images copyright Benjamin Jones.

Benjamin Jones is a contributing artist to issue 1 and issue 3 of M-A (A SPACE BETWEEN).

54. RUTH ASAWA - A SPACE BETWEEN THE INDELABLE AND EPHERMERAL.

When Forms Come Alive - Hayward Gallery - LONDON.

Ruth Asawa, Untitled, (S.065, Hanging Seven-Lobed, Multi-Layered Continuous Form within a Form with Spheres in the Second, Third, Fourth, and Sixrg Lobes), c. 1960-63. Oxidised copper wire. Private Collection. Image: M-A (A SPACE BETWEEN) 2024.

shadows drip -

awaiting surrender to pool

- a presence suspended

cages as cases of a fruit long decayed

to leave an outline - a combe - a line

as a scribbling of biro

- to blur into umbra - to form a state between the dissolving

as these drops nestle their Siamese

as a feather grows within a womb -

a scientists diagram

to rest within the dormancy of an atmosphere

rusted to inspire a russet dust

to halo these swollen orbs

elongated - by far away bulbs - to pulse a lunar tide

extruded - by fingers out of reach

undulating a waist - tender and gravid

Ruth Asawa, Untitled, (S.142, Hanging Five-Lobed, Multi-Layered Continuous Form within a Form), 1990. Oxidised copper wire. Private Collection. Image: M-A (A SPACE BETWEEN) 2024.

a pregnancy of volume

a bubble birthed within these rings

to further drip down to be caught up within -

- within these wire jars, these baskets of the collected

- as eggs that will remain unhatched

embryonic and empty

discarded shadow skins - hang suspended

dripping to pools of puddled penumbrae across an illuminated floor

- pulled up across the walls - an extrusion from within a memory

an evidence of an ephemeral rhythm to remain indelible.

Ruth Asawa, Untitled, (S.142, Hanging Five-Lobed, Multi-Layered Continuous Form within a Form), 1990. Oxidised copper wire. Private Collection. Image: M-A (A SPACE BETWEEN) 2024.

When Forms Come Alive - Hayward Gallery - Until 7 May, 2024.

53. FRANCESCA BATTAGLIA: A SPACE BETWEEN STILLNESS AND MOVEMENT.

Francesca Battaglia, London 2019.

I remember meeting you in tutorials, in those beautiful big rooms in Lime Grove, and filling my eyes with your pictures. There was always this sense of movement and the perfumed warmth of an Italy remembered - as if from a film - where characters were dressed immaculately and high drama was ushered into frame. Your image within the new issue of M-A - I feel is a very concentrated image of you, can you discuss this work and where you were within yourself when it was made?

At the time I was working on my final major project. The core of the project was the fear of forgetting, of losing memory. I wanted to focus on my roots, on my family, to be able to put together an experience and a body of work that could reassemble a story that would become timeless. I was getting a bit stuck in the process, trying to chase something deep and real that could tell a sincere personal story. I was obsessed with taking pictures of places and things. I guess my aim was to explore how to tell a story of people by taking pictures of still objects and places. That’s when this image was made. I was taking some test shots in my flat in West London in the spring. I was focusing on the still life working with objects that I could find around in the flat. My room faced a small courtyard down a basement, there was this beautiful flowery plant that had dropped and scattered all the flowers around creating a flowery carpet just right outside my glassdoor. I had found a blue plastic bag that had fallen down from the street so I took it and filled it up with all the flowers almost all already dried.

I think I realized it maybe a bit later, after leaving London, growing up, that during that period of my life I was going through a hard time with my mental health and that those images of dried flowers and pomegranates pictured also where I was within myself in that period.

The painterly palettes you return to, why are you drawn to that particular range?

I guess what I like is softness, something that is gentle and tender. I guess it’s also the palette of the places I know. Where I grew up, in the north east of Italy, near lakes and mountains where everything is slow paced and silent, the light grey of the stone of houses, the brown of the wooden roofs, the green of hills and fields. Another place I feel at home is Ibiza, the incredible colors of the island’s nature overwhelm me every summer since I was born: the red of the sun, soil and rocks, matched with the colors of pinewoods and the deep blue of the sea.

The memory of these places blended together creates my palette. And now that my work concentrates also more on portraits and sometimes capturing someone really close, I find that in the nuances of people’s skin, eyes and hair.

There is a particular melancholy that feels like a dapple of memories within your work - which I am drawn to. There is a tension there and a sense of the unresolved, which feels very poised, can you reflect upon why you depict this state and what are the questions which thread through the work?

I love how you worded it, I relate a lot to this description.

Whenever I think about a project I want it to be real, to be reasoned and sincere. I want to capture the truthfulness of the subject: an honest look, a natural slouch posture, a gesture, a crease on the fabric of what they’re wearing. I’m not into perfection and constructions.

As I mentioned in a previous answer, I’m scared of losing memory, and this definitely reflected on my urge to take pictures and make videos, which luckily growing up became my job. There is definitely melancholy, especially in my past work and I acknowledge it today in my current projects. This unfolds also when thinking about moving image. The sense of the unresolved you talk about could definitely be the thread in my film language. I’m fascinated by movement but also by stillness, on how dynamic and powerful a still frame can be. That’s why I’m probably so drawn to film, I feel so absorbed by the freedom of it and the variety of ways I can choose to tell a story. It’s not easy to describe it in words, I’m just really really passionate and I’m sure it’s the medium I’m actually more naturally prone to to express myself.

Francesca Battaglia, Piedmont, March 2021.

Your Italian-ness is again, specific to you and I greatly appreciate that in your work. There is often a tension between fashion and art, do you feel this and if so why?

Italy has of course a huge historic cultural and artistic heritage and in every part of it you can find unique breathtaking places filled with history. Sometimes it feels like the time has stopped in some places. The fact that you can feel, smell and touch something so fascinating that’s been there for centuries, it’s inspiring. This belonging is for sure very present in my work. Fashion is a big part of Italian culture as well as art. It fascinates me, I am passionate about it. I think that my way to communicate, my way to tell stories and take pictures is more focused on the subject in front of the camera, that fashion becomes almost impalpabile in my work. It isn’t explicit nor literal, it’s not the main focus, it’s part of the subject, it needs to be merged with it and tell something about it. I feel like a need to find a story in every picture I take, and clothes definitely tell stories.

You studied in London at a fascinating moment of national change, and I remember the characters within your community - together this seemed to simultaneously provoke and support your artistic development. There is often a criticism that the space between education and life after education is widening, do you feel this and if so what do you feel should change?

Yes, it definitely influenced my artistic development. I often think though that my experience was strongly affected by the rush to start so soon. There was this urgency to start university right after high school, like you shouldn’t waste a second between each step of education otherwise you could lose interest in studying, lose the moment. At least that is very common in Italian conception on education timings.

When I was 19 I remember having this feeling that I couldn’t miss the moment. I had to know exactly what my future would be, and choose right away my path. Moving to a new country in a big city, to a world so different from the small province town where I grew up, it was definitely a big step. I think it’s really important to take the chance if you have the opportunity, while you’re still fresh and eager to learn and discover, when you’re finally free to choose your way. But I also think it should happen when you really feel ready for it and when you’re more self-conscious. I think this brought in a lot of insecurities in my experience and made it more difficult to go through. While in education you can feel like you have to perform and do well and this can compromise your mental health.

This can happen also after graduating university. That space between education and landing into life and starting a career, it can be scary. When you’re a student you feel kind of in a safe zone. After education, that fades away and you’re on your own. It’s not easy to find a way to earn money doing what you love or what you studied for especially if you have to support yourself in an expensive city.

What I’ve learned after finishing my studies and growing up is that if you have passion, it’s never too late to change direction and explore something new. So there shouldn’t be pressure in choosing a path when you’re approaching education and there shouldn’t be pressure while experiencing it. Every imperfect experience builds you up as a person, but you should feel more relaxed and free regarding what you want to choose for yourself and for your future.

The personification of space is very present within your work - I remember from the early works I saw that you made, to the recent images, why do you feel you are drawn to these spaces?

I think I am drawn to spaces where I get curious, where I can imagine a narrative. I’m also really fascinated by architecture, how a space is designed and its history. I try to imagine what stories a place holds. Sometimes I wish I could see what happened there in the past, through the years, imagining stories of people. It really fascinates me. And I’m always attracted to details that sometimes aren’t noticed.

I attribute a special meaning to some places, and I want to keep them impressed in my memory, sometimes there are places I just pass by and I know I won’t visit again, sometimes they are very familiar in my present but I know someday I won’t see anymore.

For this reason, I use photography in a kind of obsessive way, always taking pictures on my phone when a detail captures my gaze.

Francesca Battaglia, Lombardy, Summer 2018.

Francesca Battaglia is a contributing artist to issue 3 of M-A (A SPACE BETWEEN).

52. JOHN SINGER SARGENT: A SPACE BETWEEN ART AND FASHION.

Sargent and Fashion - Tate Britain - LONDON.

John Singer Sargent, Polly Barnard, 1885, sketch for ‘Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose’, 1885-6. Tate.

The bobbing of paper lanterns and the witnessing of a swarm of tiny unfurlings - illuminating the glosses of lilies - popped open, the micro parasols - weighted in pollen, sticky with scent. And the roses, abundant and scattering of their harvest of petals - delicate and a chatter with brushstrokes gleaned from many gloamings.

An upstep of heel treading the violet dust of an imagined earth.

To capture cloth as if to listen to its very fibre - of impressions more akin to murmurings than definitions - lapping, pearlescence of a purring, bubbling calm.

His romance is to engulf, to suspend and to flush -

A corset laced so tightly - a bosom of blossoms - a fluttering of clementine ribbons - and yet the swathes of blacks, charcoals and ebonies envelope with descending cloaks of the impending.

John Singer Sargent, Sir Philip Sassoon, 1923, Oil on canvas, Tate.

Fashion - the audaciously tardy teenager - lost within their love of the fleeting, the door-slamming demands for attention and the special treatments negotiated for the rewards of such mysterious beauty and eternal youth - where the alignment of silhouette, fabrication, and atmospheric timing play a poker match of tactility.

John Singer Sargent, Portrait of Mrs Leopold Hirsch 1902, Oil on canvas, lent from a private collection.

And to art - somehow nobler, wiser and calmer? And so, more reliable and respected? And because of this, somehow more bankable even controllable? John Singer Sargent dares to occupy both trade traits with the fascinating directness of not just the artist but the art director - who employs, even tames the perfected technique to present and seduce without conceptual weight. As then and now, Sargent's target audience is consumer lead and in so doing he protects a legacy as a creator and also as a service industry - a bridge between two industries - where every subject surely leaves a happy customer. However, as with trends of technique rooted in time, the shelf life can form an obstacle when viewed in retrospect.

It is this, the often overt impression of fashionable success that Sargent perpetuates through his work - that somehow falls foul of the art world’s cardinal oath of a confessional truth confided by the noble artisan who suffers alone, and for all the implied champagne cork pops of Sargent’s atmospheric belle époques - it is sometimes hard to follow the script. His subjects do not appear to depict the dour, devoted disciples of faith as the jeweled-toned clouds of Titian's subjects suggest or the patron saints of the noble as favored by Velasquez - Sargent dares to centre his illuminating brushes not on celebrating faith but instead on fashioning celebrity, utilising the techniques of the brotherhood of artisans who proceed him, and this is his conceptual provocation.

Viewing these works today - Sargent’s ability to seemingly weigh hearts against feathers - feels faux - deep down, as he entertains with a classism that is loaded for the loaded, exclusive, and excluding, as all great fashion is - unforgiving and tailor-made to flatter the benefactor alone, however admired. Conceptually provocative when considering the means for which some such Victorian fortunes were amassed, who patronised Sargent’s ability to render his subjects as meaningful even iconic. This bookable Midas touch, entertains - but does not, fully convince - to modern eyes perplexed and weary of news-stories whose heroines do not have the choice to wear their hearts on such haute couture sleeves.

And yet, just as the great fashion makers know, it is in the juxtaposition that the tension, the catalysts for change lives. Sargent is surely a signaling influencer to each of the societal tastemakers who follow his legacy, in the camp of Cecil Beaton's charm, in the noble stature of Richard Avendon's knowing reduction and in the impossible drama of Annie Leibovitz's filmic knowledge of the jarring - a lynchpin in a style, which defines modern portraiture.

Jean Philippe Worth for House of Worth, Woman's Evening Dress, around 1895. Silk damask. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Gift of Mrs. J. D. Cameron Bradley.

Sargent and Fashion - Tate Britain Until 7th July 2024.

51. NATHAN VON CHO: A SPACE BETWEEN THE BOW AND THE STRINGS.

‘I really wanted to be a vessel: M-A speaking through my violin and I.’ N.V.C

Nathan Von Cho photographed by Eva Vermandel, 11th January 2024, London.

Before I ever heard you play I saw you play, when we walked into the David Zwirner gallery for the first time, you closed your eyes and performed without a physical violin. I found that to be fascinating - watching you play I was amazed at how both physical and metaphysical the process of creating and performing music is... can you expand upon your creative process?

David Zwirner has such a unique presence about it and I also noticed that my speaking voice carried like we were in a church. I guess as soon as I found out the position I was going to play in, without much thought going into it, I naturally closed my eyes and imagined how the violin would complement the acoustics of the Gallery. This way I know what I can get away with and how I bring the space and violin to life.

Nathan Von Cho, David Zwirner Gallery, London, December 2023.

Your relationship with your violin is very particular, I remember you saying that there was a period of time when you wanted to reject what you knew, and yet you chose to perform with it - can you tell me about Nathan and the violin?

My violin has been my partner in crime for more than 20 years and I actually cannot imagine a world without it. Of course - having gone through childhood & my teenage years (maybe even up to my early twenties) I had my battles where everything else in life seemed so much more appealing. Be it rugby, friends or just anything that was not the violin. They even wanted to take away my music scholarship back in secondary school because I was that distant from it but my violin teacher at the time Mr Burov, stopped the music department from stripping me of my scholarship saying: "just wait, Nathan will come back to the violin" and I think this quote sums up my relationship with my instrument very accurately. Looking back, I was extremely lucky with all my violin teachers. They really filled the father role for me growing up which I in retrospect, desperately needed. It was more than just violin lessons, now they are beautiful memories for me so, as I also teach music, I try to carry the message as I was shown, ‘from the heart to the heart’.

I knew that I really wanted you to be involved with the opening ceremony of the new issue of M-A because you have an energy that is rare and urgent. A contagious energy that I first encountered last year. I asked each of the artists presenting to choose an image from issue 3 to reinterpret in their own way - your choice was fast and fascinating - can you recall the process of developing work for Thursday 11th January?

I do remember that moment and process. Yes - it was indeed quite fast and I was torn between two images for a brief period but I really like the style of the main character, (Boy with Pink Aerosol, Stroud Green, 2006, Eva Vermandel) the cap, the jawline even. Something about that image was screaming inside me that I could relate to, the style and the colours. One quite amusing fact about this process is that only after I chose the picture (three days before the event to be exact) I realised the boy actually looks like he is playing the violin! It could also be a phone but obviously, the first idea appeals to me more. There is that sense of brushing someone away, multitasking or even impatience and you mentioned that my energy is urgent (which is a word I haven't heard before to describe me) and the boy in the picture - looking at it now has - definitely an urgency.

There is evidently a lot of discipline which is invested in the pursuit of mastering the violin, so many rules and yet you seem to break down these rules when you play. That particular feeling of suspended charge that comes with the risk-taking of adventuring off-piste, which your audience was transfixed in witnessing - can you expand on the relationship with boundaries when you create and perform?

If I had to use one phrase to describe the event or even my life, it is "rule-breaking" not always in the most artistic of manners as I almost got kicked out of school for not adhering to the rules. You specifically asked me to wear what I wanted and be myself (when I performed`) which for a classical musician is not something you hear every day. I feel like classical music at the current stage is like a 5-course meal and sometimes you just want a snack. I would like to be the bridge to make classical music more accessible and for people to approach it lightly without having to mentally prepare or take out 90 minutes of their lives. Going back to rule breaking, I only really composed the first 4 lines of the melody and for the rest, I just let something else channel through me so if you ask me to repeat what I did on the night: I probably couldn't. That is the beauty of it where it is something that won't be recreated exactly. This event definitely was an eye-opener for me to really just go for ideas I have in my head because that space, the present moment sharing with my fellow performers & the audience. I really wanted to be a vessel: M-A speaking through my violin and I. One last point to make would be engaging with the audience. Not in a talking to them verbally kind of way but feeling out how full the space is, how much of the sound they absorb and how much I can push, and what I would like to do, which at the time, is just in my head until the bow meets the strings.

Culturally you are diverse in your lived experiences, South Korea, Berlin, and London - how have you been influenced by your journeying through these spaces and how have you explored this knowledge within your practice as an artist working today?

I am super grateful to have had the opportunity to live in different countries, mix with different cultures, and be a part of religious cultures from where I do not originate - but on top of that - one common denominator, they all have is music - in my experience, the violin. Having a Russian Guru who was only in Berlin due to half of Berlin being split due to historical & political circumstances, playing for Jewish weddings growing up, speaking Hebrew and even playing for the Royal family's Christmas reception. These are experiences and influences one cannot take for granted and have affected my music-making massively.

Nathan Von Cho preforming with Zaineb Lassoued, Callum Helcke, Max Shoroye, Xiangyin Cho and Nandi at the launch event of M-A (A SPACE BETWEEN) issue 3, David Zwirner Gallery, London, 11th January 2024. Photographed by Sunny Sun.

Special thanks: Eva Vermandel and Sunny Sun. Sara Chan and Aoife Kelly-McCann - David Zwirner.

50. YOKO ONO: A SPACE BETWEEN MAXIMUM SILENCE.

YOKO ONO: Music of the Mind - Tate Modern - LONDON.

Yoko Ono, Sky TV, 1966. Photo Cathy Carver. Courtesy of Hirshhorn Museum.

A typewriter - embossing without a ribbon.

A call for response where no reply is needed.

'Hello this is Yoko'

A harmonious gloom of shadows cast from a caste of chairs requires no impression.

Paintings of unfinished shadows, of water droplets - of whispered - imagined instructions and collected skies.

'A frame of mind, an attitude, determination, and imagination that springs naturally out of the necessity of the situation.’ Y.O.

John Cage and Yoko Ono performing ‘Music Walk’, Tokyo 1962. Image courtesy of Sogetsu Foundation.

Cut pieces away - while I watch you - while you watch me and while we never make eye contact. To hold these scissors and to practice an invited assault while an instinct is over-ridden - while my heart beats faster. Take whatever you want to take not what I want to give.

To slice through a life with a katana precision, as to reek the domestic - ridiculous, unliveable - when viewed in surprised retrospection - with an understanding of maximum silence.

To soak hands in this stillness and stare out - through the fourth wall, looking for the collaborator, the other half of a puzzle never to be solved or completed. These pieces await and yet it is the space between which is more present, more painful than these creamy-coated souvenir souvenirs - these severed props which began as a comedy and conclude as a tragedy.

An invisible city built in perspex, audacious in adolescence - now chipped with the wounds of removal and the evidence of provenance.

This distilled metropolis, whose light-less structures cast an impression, not a shadow.

Atop this rooftop penthouse - rests an apple totem - perpetual in life - symbolic in renewal.

The iconography of the implausible, of egoless empire - of tart temptation - a readygrown - readymade, whose skin will never wrinkle and whose flesh will never feed.

Installation view of Apple 1966 from Yoko Ono One Woman Show, 1960-1971, MoMA, NYC, 2015. Photo © Thomas Griesel.

From these imagined constructs - a view can be felt, a horizonless landscape sustained, as a scudding of daydreams fill forever blue, where 'you can eat all the clouds in the sky' and where the sunsets last for days - and yet an internal starless darkness persists - as molecules of ink - circulate as a pointillist's insistence, in a tapping which collectively leaves a tattooing trace and a jarring humm in this silence - to freckle a skin of touches.

'Molecules are always at the verge of half disappearing and half emerging...to wear different hats as our heartbeat is always one.' Y.O.

YOKO ONO: MUSIC OF THE MIND - Tate Modern - Until 1st September 2024.

Special Thanks Anna Overment and Kyung Hwa Shon.

49. SUNNY SUN - A SPACE BETWEEN AWARENESS AND RESTRICTION.

‘Do I need to be objective about something I don’t feel is quite right?’

S.S.

Image courtesy of the Sunny Sun.

We were talking recently about the notion of not needing to be convinced - when something feels right, can you expand upon this idea and how it relates to you?

I realised when I speak to others, who like different things, they always try to convince you with their point of view, the reason, a different understanding and insight. No matter what they say - they can’t really convince me - everyone seems to try to be neutral in different circumstances, but is that really possible? I start asking myself ‘Do I need to be objective about something I don’t feel is quite right?’

The attractiveness or reluctance of anything comes from the thing itself, not from how anyone tried to explain/justify it. So I believe no one can be convinced, or anything can convince anyone, if anyone has an opinion I guess it cannot be explained. But at the same time when things are good enough, your instinct will feel it.

Image by Sunny Sun for M-A (A SPACE BETWEEN) 2021, as seen within issue one of M-A (A SPACE BEWTEEN) 2021. Still life image: Harry Nathan.

You know I love your photographs, your contribution to issue one of M-A was so distilled, even private and yet your pictures have a specific generous quality which seem to welcome interpretation.

The series from Hong Kong feels so strong, the sleeping father, the granular city in the scorching heat of August... when you look at your work what do you see now?

Umm, Joe you know I never take photography seriously just like a ‘photographer‘. Always out of focus, films out of date, or even with a random camera. I started picking up shooting images (won’t say photography as I don’t think it’s proper) when the mood comes, My mother playing mahjong, capturing the sound that I got so annoyed as a kid that eventually I felt at home hearing it. Or my father sleeping on the couch (just like a mugshot, no shame but scared at the same time). When I first started to take images, I felt the struggle between trying to be brave, and the reluctance of pressing the shutter. Once I pressed the button, everything stopped within that image, no idea if it is overexposed, or even if anything comes out. I guess that’s the tedious journey of being with film without doing it properly, the instinct of that split moment, no idea, not feeling secure. But that nervousness captured how I felt at that time, its abstract and intimate that only myself will feel.

Now I look back by the perfectly edited down images, I felt thouse nerves, the struggle to make my mind up. It’s just like looking back to the first word of a public speech. Maybe I meant something maybe it didn't, but looking back what’s real and what’s not? I guess going back to being convinced or not I am glad the audience felt differently from the images, they probably find more values in those images that I did while I took them. I find that quite fascinating.

I had a first look at the first series of M-A, and I said that this is the only tactile media I’ve read in my life that makes me want to flip back and think what exactly is this? I recalled looking at my images - I almost forgot what I’ve taken. I guess I wasn’t convinced, the images convinced myself or others of something else, memory stayed intimate to myself. You see, no one knew it was my father...

Image courtesy of the Sunny Sun for M-A (A SPACE BETWEEN) 2021.

Image courtesy of the Sunny Sun for M-A (A SPACE BETWEEN) 2021.

You are a designer also, and you favour a very discreet aesthetic that resonates with a respect for materials which you seem to see almost like ingredients... There is a certain shrugged on invisible - gentle quality within your own identity and your images reflect that - can you trace back to the key moments in your life which have helped form the way you see?

I was never shown as a masculine person, I like feeling humanity, being free flow. Feeling material and craft but also knowing the fact that there are some sort of invisible rules. Images are the same, I recalled myself saying, my images have to be film, but in a P&S camera with no settings, I like to set myself rules but nothing looks stable. Of course from time to time I stopped using film and I just have that awareness of restriction inside me and again, every images comes out as random as it looks. The formal sense is hidden to myself, same from taking pictures, to the clothing I like, or the things I want to design really.

Image courtesy of the Sunny Sun.

Your loyalty to your own instinct is probably the thing I respect most about you, and I know that people in your circle feel the same way, you are the go-to person to ask about sourcing. In fact I think the first time we met you were striding through a studio triumphantly holding a double-faced tweed coat from Jil Sander in one hand which you had freshly acquired and had already secured a buyer - your ease in acquiring amazing things is certainly a talent, do you remember the first objects you started to collect?

Aha, the Jil Sander, was a steal back in the day and reselling since I knew I won’t be wearing it!

I guess I like to understand products and items from the second-hand market, and how it was worn. I always believed that clothing is like a tech, its existed to be used, and to be felt and to solve problems.

Not only what I buy and wear, as an accessories designer, we love to collect materials, hardware or tools. We appreciate them and think how it can be enhanced, or even solve problems in a design/product perspective. I love factories and rustic sourcing markets, they are people that fulfil our fantasies, solve the problem that we wanted to be solved. Designers are there to solve problems, not only practicality but also aestheticly, I guess that’s my core and that’s why I love participating in sourcing too.

I remembered the first ever thing I really started to crave and buy multiples of were Tricker’s shoes. I really liked the shapes, and everything. But eventually I stopped wearing them, and looking back - how on earth I wore them - so rigid and heavy, and travelled everywhere? Except being so hard to wear in at first, Tricker’s shoes are a wonderful piece of tech.

Image courtesy of the Sunny Sun for M-A (A SPACE BETWEEN) 2021.

Your returning to London always interests me - even when you are not there your mind seems to be in some way there, what is it about the city that resonates within you?

London means home to me, I’ve been here for 10 years. It’s great to feel, revisit and explore the city, it’s always cinematic, passionate in some ways and quite special despite the fact that more and more people rant about London.

I’ve been living in many cities and I miss and fantasise about london a lot. This time I’ve moved back - I am not a student. I feel that London makes the majority of us special - We are all enjoying, expressing and struggling...

For me London gives you things that cannot be bought with money.

Image courtesy of the Sunny Sun for M-A (A SPACE BETWEEN) 2024.

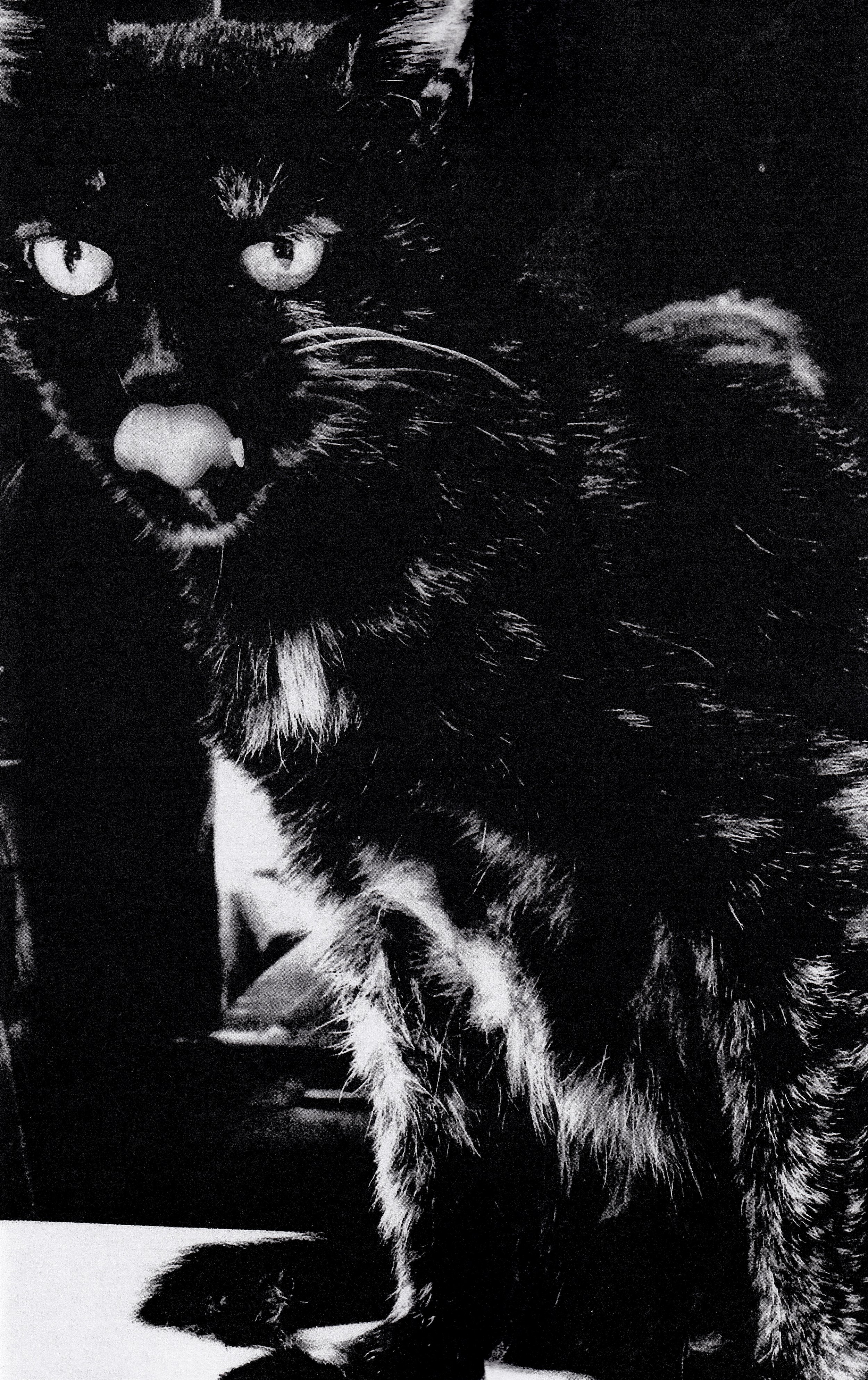

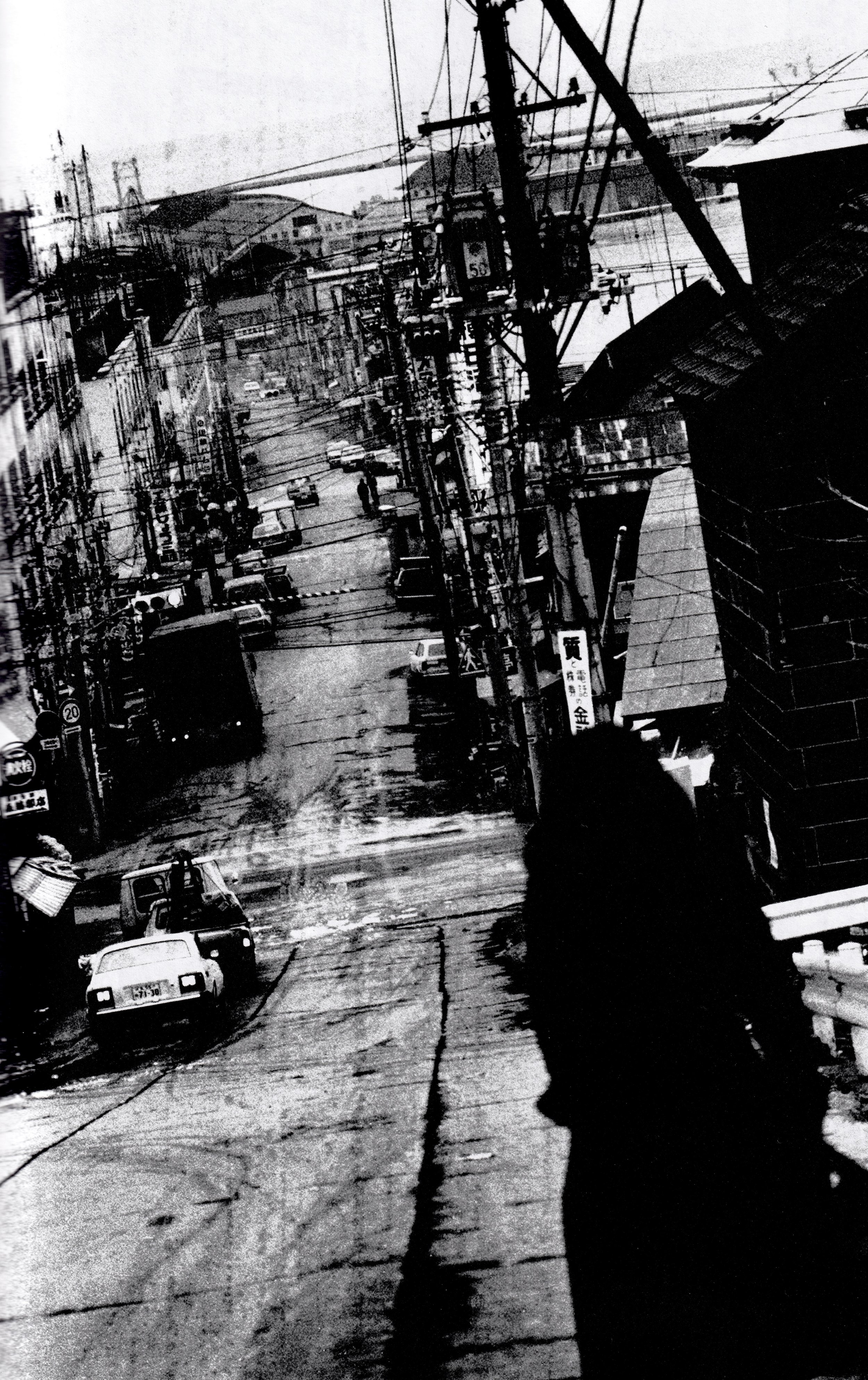

48. DAIDO MORIYAMA - A SPACE BETWEEN DESIRE AND TERMOIL.

Daido Moriyama: A Retrospective - The Photographers Gallery - LONDON.

Daido Moriyama.

A blur of an unknown street, exhausted tulips surrender, teeth lick, 'I am constantly observing the city', 3am naked, electric light and black shaddows. Araknid paused - ready to scuttle, the exposed metal intestines of a motorbike,

Daido Moriyama.

footprints in the slush, mesh, fish-scales, tiles undulate,'People's desires are endless'. Rubber tires tessellate, stockinged legs, gated fences, observed encounters, tarpaulins sweat, the mannequin severed, all become equal. The

Daido Moriyama.

signature granular of the ingrained, the arousal of the saturated violence of colour, occasional, the darkness of death.'The human world is erotic' Behind glass - laid out as if awaiting a chalk outline - relentlessly passive probe

Daido Moriyama.

printed pages overhead and overheard Moriyama murmurings.'I am always in a state of emotional turmoil' The plethora of an unshelved library - damp as if the first things saved from a fire - neatly, calmly awaiting the next viewer, the next

Daido Moriyama.

voyeur the next body. Forensic and cold to touch, burnt into paper - exotic in weight, erotic in tender - like cigarette paper or cicada wings - cut - cut sharp - detached. 'I don't feel at ease when I am shooting' To inhale these

Daido Moriyama.

sticky sheets is to see the secrets, to feel these ferals, which glisten and undulate with a painful ferocity - tiny breathing dialogues, caught in a

Daido Moriyama.

viewfinders' trap, hooked on an inky intimacy, still wet - so close - the eyelash brush of his window cannot be unseen.

Daido Moriyama.

Daido Moriyama - A Retrospective - The Photographers Gallery - 16-18 Ramillies Street, London W1F 7LW. Until 11 February 2024.

Special thanks: Martin Steininger.

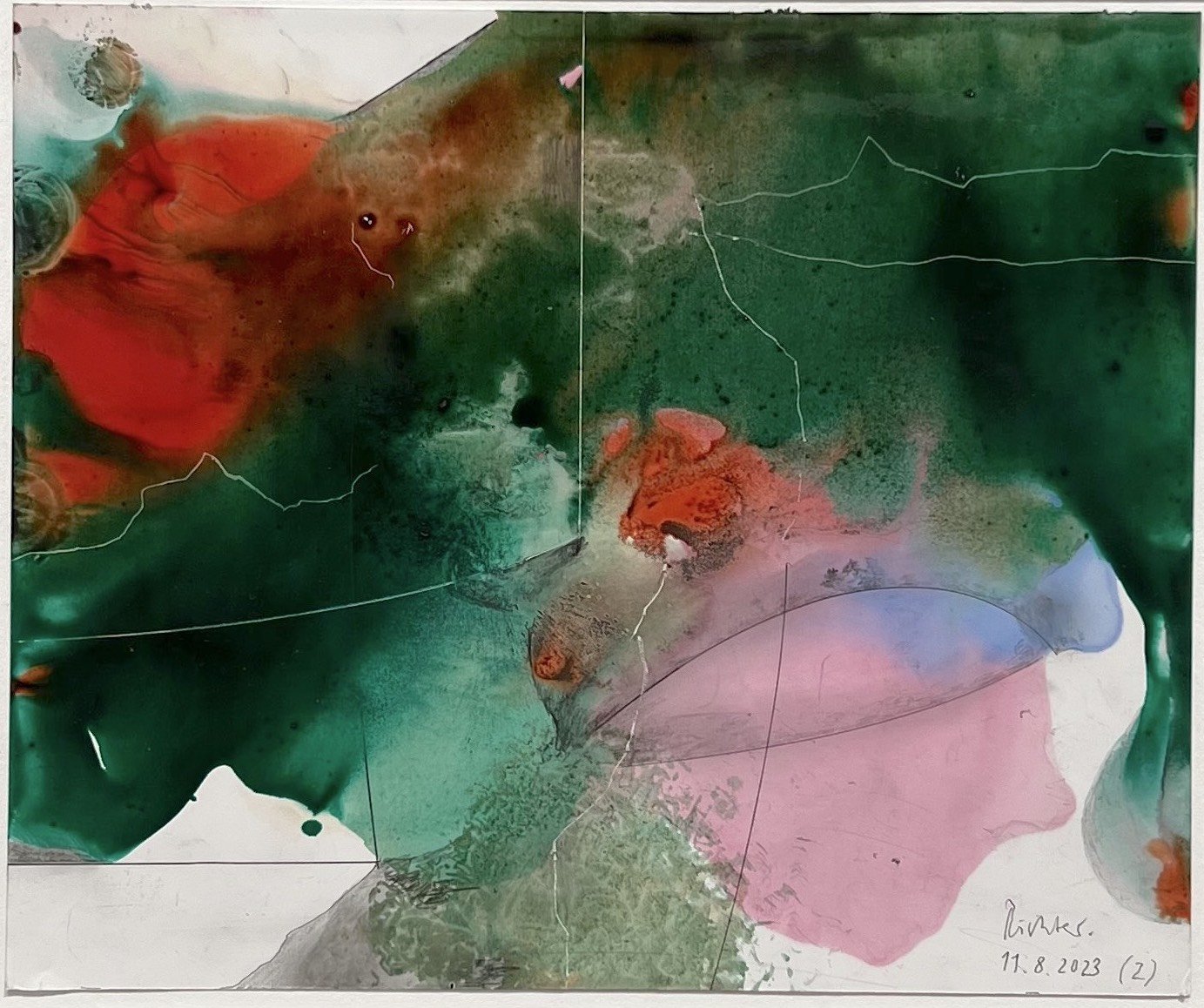

47. GERHARD RICHTER - A SPACE BETWEEN DISARRAY AND ALMOST NOTHING.

Gerhard Richter - David Zwirner - LONDON.

Gerhard Richer 12.8.2023 (4), 2023 - Coloured ink, and pencil on paper 21.5 x 26 cm. David Zwirner, photographed by Zhonghua for M-A (A SPACE BETWEEN) February 2024.

Spluttering, undulating clouds squashed between glass - as in a microscope - a slide - analysing life - the beginning - made towards the end.

a micro-line ticks forth as on a graph - connecting dots - a constellation - charting a course.

A map viewed from above - where colours indicate symbolism, shading regions and masses darken depth.

Landlines cut into a terrane - exposed in the full flow of controlled volatility, the diagrammatic splicing of a leaden cloud.

The marking, amorphous of meetings - of melding, of bleeding and healing of reaction and action to erasure.

Of minerals under scrutiny of an eagle's eye, sawing above - the telescopic range of NASA - the cosmos overwhelms yet ignites - a steady hand at mission control. A world beyond - a world within - all is made of such matter. To The unblinking of these emerald pools -

Gerhard Richer 3.8.2023 (2), 2023 Coloured ink and pencil on paper 21.5 x 26 cm. David Zwirner, photographed by Zhonghua for M-A (A SPACE BETWEEN) February 2024.

- a dilation - where inks bleed and freckle a genus.

These micro graphite configurations - a psychiatrist's analysis - the tracery of the barely, an outline to define an impossible - an almost nothing.

A flushed roomscape emerges from a swathe of washes - as a tide draws back - exposed the headlights of passing in the night - a still from a progression - a sequence of future memories - as such clouds engulf these sunsets - the phosphorescence - these shimmering auroras. The ruin of a drop to further dive into the green - the validifying context of chance - the chance of a master of control - now swimming in the night - why now to revel in such encounters?

To scour the surface at right angles to counter and encounter this organic. To appraise these meetings of ink and paper of then and now.

Such subtle tenderness - catching colours - unexpectant of the violence in plain sight - volatile, momentary and permanently scared. - Scratched insertions disrupt the near-solidified solutions in their final moments of lucidity - to drag back a surface to expose an emergent - chalken line of the vulnerable - not ready to be set in stone.

Gerhard Richer 11.8.2023 (2), 2023 Coloured ink, ink, and pencil on paper 21.5 x 26 cm. David Zwirner, photographed by Zhonghua for M-A (A SPACE BETWEEN) February 2024.

A crackling through the shellac glosses of the sealed in the semi-permanence of a reign storm - to reach a relief from the impending.

The occasional bubbles escape the depths to reach the surface - to flush with blushes of remembrance.

Presented from behind the engineered - graphite frames of the creator's vision - looking out - looking within. Crisply defined as the sheets of identical paper, a ground of snow where horizons meet the sky - to trace the silhouetted clouds from a child's eye.

“What characterizes drawing even more obviously than painting is the sense of disarray, the absence of a way out.… Drawing is … an erasure, an almost nothing, right at the extreme edge where everything would fall into pieces. Just before then you stop.”

— Gerhard Richter, 1997

Gerhard Richer - Strip, 2013/2016 Digital print on paper between Alu Dibond and Perspex (Diasec) Four (4) panels, each: 200 x 250 cm overall 200 x 1000 cm. David Zwirner, photographed by Zhonghua for M-A (A SPACE BETWEEN) February 2024.

Gerhard Richter - Until 28 March 2024, David Zwirner - 24 Grafton Street, London

Special thanks Sara Chan and Kyung Hwa Shon.

46. MASAOMI YASUNAGA - A SPACE BETWEEN HOLE AND WHOLE.

‘Clouds in the Distance’ - Lisson Gallery - LONDON.

'Beauty can be discovered in the most unconventional situations.’ M.Y.

Masaomi Yasunaga photographed by Sunny Sun, January 2024.

A psychological archeological haul, presented in the blinking daylight of a time in delay - like the memory of touching the clouds, as a child.

A time machine's contents where such relics are scoured for answers, seemingly created in the depths of a darkness - their inward eyes baked shut, their heartbeat too slow to hear, but to touch these tremulous barnacled bodies is to sense that their kiln birth - forever warm. A grandmother’s ashes form a porcelain memory - crystalised and hot with tears to dissolve into the porous.

To hatch the insects and protruding bones of a ruin. A construction of rubble, where foundations are absent and the ceilings cave.

'When I create, I always envision a distant view, an act of seeing afar'. M.Y.

Masaomi Yasunaga, Vessel Fused with Stone 2023, Glaze, Coloured glaze, Glass, Coloured slip, Kiln wash, Granite, Kaolin 82 x 70 x 70 cm. Photographed by Sunny Sun, January 2024.

These unearthed - amniotic fluid glazed jars hold their holes to cast internal beams in a dormancy of rest - vacant, abandoned yet meniscus full - all these nothings have meant more to me than so many somethings - The escaped or rolled back stones expose the gaping of the dropped granites of the monsters bite - such teeth marks afirm that the space is greater than the sum of such parts.

'Beauty can be discovered in the most unconventional situations.’ M.Y.

Masaomi Yasunaga,‘Empty Creature 2023 - Glaze, Coloured glaze, Titanium oxide 17 x 22 x 10.5 cm. Photographed by Sunny Sun, January 2024.

Poisons bubble, spurt and splinter to hue a mosaic of excavated evidence - formed under the pressure of violence, of ego and the melted prestige of fallen kingdoms - relics still stunned in stillness - once lucid and undulating - now brittle and dry, exposed on a beach awaiting the tide to conceal, to return.

'The ultimate goal of my art is not self expression but what's left of self, after being filtered through fire'. M.Y.

Masaomi Yasunaga, Melting Vessel 2023, Glaze, Kiln wash, Kaolin 31 x 22 x 21.5 cm. Photographed by Sunny Sun, January 2024.

Masaomi Yasunaga ‘Clouds in the Distance’ - until 10 February 2024 - Lisson Gallery - 67 Lisson Street, London.

Photography Sunny Sun for M-A (A SPACE BETWEEN)

Special thanks: The Lisson Gallery.

45. EVA VERMANDEL - A SPACE BETWEEN CALLING AND CAPTURE.

The artist discusses her creative process.

‘I do wonder sometimes whether I’m just a vessel that captures things that get sent to me and need to be caught.’ E.V.

Eva Vermandel, Boy with Pink Aerosol, Stroud Green, 2006. Image courtesy of the artist.

The first time I saw your works, I was immediately amazed at how you communicate emotion - images that are so luminous they can be seen when the eyes are closed - at what point did you know that photography was your way forward?

Thank you so much, emotion is what I try to communicate so it’s incredibly gratifying to hear that that is what you take away from my work, and so intensely.

I was about four-five years old when I first picked up a camera. My father was an amateur photographer and we’d often go for walks together with his camera in tow. He’d occasionally let me take a picture with it. Back then, in the late 70ies/early 80ies, photography was precious and expensive, so this was done sparingly, we were not a rich family. By the time I was a teenager, my dad let me use his Contax to shoot the odd film, and the curious thing is that the pictures I took back then have the same intensity and atmosphere they still have now. So I think it came embedded in me.

Eva Vermandel, Bart, 1988. Image courtesy of the artist.

That said, I’ve often battled with the actual medium of photography, with its directness. The art I get drawn to most is painting. There’s such a freedom to bring the emotion of an experience to the fore in painting, rather than the de facto ‘this is what occurred’ element that often gets represented in photography. The result is that my practice revolves around breaking through the directness that is inherent to photography.

For years I found this directness a restraint, and up until a couple of years ago I did toy with the idea of switching to painting, until I realised that my battle with the directness of the medium is what makes my work so singular. I revel in pushing the camera to its limits, and this often happens not through special effects but simply through intense observation. This can go so deep that I feel that it is me who is being swallowed up through the lens, rather than the other way around.

Over the years I have become aware that I don’t ‘create’ my work, but that I ‘catch’ it. The sharpening of my craft lies in training my instincts to feel these moments brew and trust that whatever it is that needs to be captured will get thrown in my direction. Even on the few occasions that I have worked in a constructed manner, there will still be elements within that constructed setup that guide me rather than me guiding them.

'Boy with Pink Aerosol' seems to be such a pivotal image, how did that portrait come into being?

I personally wouldn’t call it a portrait, rather a state of being. At the core of the image lie the gestures of the arms, which are both engaged with elements you can’t see, and the tilt of the head and neck. There are also details that are so slight that the viewer needs to fill them in. It’s a puzzling work and it requires active looking. I love what Francis Bacon said about art: “the job of the artist is to deepen the mystery”. I fully empathise with that.

It happened upon me in the summer of 2006, when I had gone for a walk with my Mamiya 7 near where I used to live. I came across a group of teenagers spraying graffiti on a section of Parkland Walk, north London. This is a disused railway track that is now a nature reserve and favourite haunt for locals. Several of the leftover structures of the railway get graffiti-ed on a regular basis and that afternoon these boys were having a go at it.

I asked if I could photograph them. I remember that the boy in the photograph is called Phil. He had an elegance about him that drew me to him more than the other two boys. I think he must’ve been around 16 at the time, so he’ll be well in his thirties now. I deliberately underexposed the negative to get the background to drop away and to enable his skin, which was luminous, to become even more radiant.

The post-production of this work was as important as the creation of the work itself. To achieve the depth of the luminosity of the skin, the underexposure of the negative was pretty extreme, about three stops; afterwards I had to rebuild the parts that had nearly disappeared. All in all it took me about five years to get it to a point where it felt right. It’s not the only work that took me years to finish.

I love the fact that it can take me years to get a photograph ready for print. It reinforces the long-time-frame undercurrent of the work. A lot of artists I admire have elements of this in their workflow too: Edvard Munch often reworked his paintings or revisited the same theme/setup he’d painted before. He once said “I don’t paint what I see; I paint what I saw” which resonates with me immensely. He’d spend hours just sitting opposite a person, not touching his canvas to then paint them after they’d gone. The galloping horse he painted in 1910 was done from memory. He must have deeply absorbed what he saw in those split seconds that it was happening to be able to paint it in such a dynamic way afterwards.

Edvard Munch, Galloping Horse, 1910-1912, Oil on canvas, 148 x 120 cm, The Munch Museum, Oslo.

Pierre Bonnard is another example of prolonged-time artists: he’d show up at the opening of his own exhibitions, brush and paints in hand, to add more touches to the works installed on the wall. Or he’d repaint a whole section of a painting years after its initial completion. He’d ask sitters to walk around as he was painting them, which enabled him to shift the focus on the rhythm and colour of the work rather than the ‘likeness’ of it. One of his sitters, Dina Vierny, said that he asked her to walk all the time; to ‘live’ in front of him, trying to forget he was there.

You need time to process what is happening AND life is in constant flux. These two factors combined mean - for me at least - that art needs space to breathe and will never be, neither should be, ‘finished’.

The title of your book, 'Splinter', is fascinating, the idea that elements of a whole can fracture and get underneath your skin - I really feel that within your works. What are the key images that you return to within your collection and what do they tell you?

Thank you, yes, the name Splinter was suitable for the work. It has many ways of interpreting it, which I like. Aside from the splinter as something that gets underneath your skin there’s also the fact that a splinter comes from a tree, a beautiful thing (trees are such a joy!). Then there’s also the feeling of being splintered. And there’s the famous Adorno quote: “The splinter in your eye is the best magnifying glass available”. It’s such a versatile word that can be used in so many different contexts and interpretations.

In terms of what the key images in my work could be: these often change. Over time works that were key get overtaken by other works and then things change all over again. The work is never static, it keeps evolving, within the existing work and in the process of the creation of the work.

This is also why Giorgio Del Buono of Systems Studio, who designed my website - and did so most beautifully and insightfully - created the randomisation of the Selected sections on the site. I love the way that every time the page gets reloaded different images will be thrown together: through this process new elements you - or I for that matter - hadn’t spotted before come out through these randomised juxtapositions.

As to ‘Splinter’ as a book, I now see it more as a collection of early works rather than a ‘project’ or ‘body of work’. I’ve completely stepped away from the ‘project’ approach that is so prevalent in photography. When I put work on display I like to mix up pieces created throughout my whole practice, old and new. New work can add a whole different dimension to older work and vice-versa; there’s always a dialogue: within the work, between the work. I find the idea of a ‘project’ far too constrained and it doesn’t fit with my thinking.

To get back to the point of key works: even though they often change, there are some works that were turning points in my approach to the creative process. One such work is Tree, Stroud Green, 2014, Which came into being because it had to: I could feel it calling me as I was walking down the street I used to live on. I got my point-and-shoot Contax T3 camera ready (which I started using for my artistic practice around that time and always carry with me) and when I turned the corner it was there. I even remember thinking “ha! It was you that was calling out to me!”. I took a couple of shots and walked on. The piece that came out is one I’m very fond of.

Eva Vermandel, Tree, Stroud Green, 2014. Image courtesy of the artist.

At that time I needed to break away from the aesthetically pleasing painterly style I’d mainly been working in up till that point. I needed something harder, something that would be both appealing and repelling. I do not like complacency in art, not as a viewer nor as a creator of art. This need to push boundaries does not come from the perspective of “aaah today I’m going to do something different, something subversive”; it comes because at some point the work calls out that this needs to happen. This image came into being because it had to. It ‘presenced’ itself and I caught it.

I recently made a film in collaboration with the composer Galya Bisengalieva, shot on my iPhone, an old SE. Once again, it was a case of something brewing, an invisible thread that I needed to follow. This came about through Galya’s invitation to create a film for a track on her album Polygon, which, after a couple of weeks of letting the music sink in, led to a first spontaneous piece shot from a double decker bus for the track Degelen. This set things up for further technical explorations on the device I was using and - finally - another ride on the same bus, the 197 between Sydenham and Peckham. It all built towards the film I landed on in the end, shot during that second bus ride, which is uncanny in its timing, composition, eeriness and perfect syncing to the music. It baffled both Galya and me afterwards, how deep the synchronicity is between the film and the music, and I can still barely believe it all came together the way it did.

Galya Bisengalieva - Degelen (Official Music Video)

I do wonder sometimes whether I’m just a vessel that captures things that get sent to me and need to be caught. It’s a funny thing to build a whole practice on chance; on sharpening the intuition to grab things rather than actively setting out to create work from scratch. It requires a leap of faith which I relish.

Your images evoke so many senses and yet you are known for creating photography, have you expressed your instinct through other media?

Oh yes, see above. I sometimes paint, mostly in watercolours. I recently did an audio-piece for an exhibition I had in Amsterdam in April 2023, and am working on another one for a future exhibition, and I’ve done three films up till now. As with everything, these things came about because they presented themselves to me in some way or other.

The three films I’ve done were shot using completely different tools: 35mm film, a Nikon D800 and my iPhone SE.

The first one, The Sea Is Always Fluid, with Aidan Gillen, was shot on 35mm. It had cinematographer Rachel Clark on camera and was one of Rachel's first films as a cinematographer back in 2011 (she now shoots feature films, among which I Am Ruth with Kate Winslet and her daughter Mia Threapleton last year). It came about because Panavision had offered Rachel a whole 35mm kit rent-free and she was looking for an opportunity to use it. I’d known Aidan for a long time (we used to see each other) and felt I’d never been able to capture him as I’d wanted to in a still. I especially wanted to capture his connection with the sea. I’d just had a good year financially so could afford the costs involved in a production like this (despite the camera kit being free, there was the insurance, transport, accommodation, processing etc to pay for still).

I had plans for what I was going to film, because when working in a setting like this, with all the cost involved and a whole team (Aidan, Rachel and the two camera assistants Tim Allen and Alejandra Fernandez) giving their time for free, you can’t go “ooh I think I’ll just see what happens and improvise on the spot!”. It was - of course - the spontaneous, everything-falling-into-place footage that we shot right at the end of the day that became the piece. The sun was setting, the sea had pulled back and formed a mirror on the shore. Aidan lay down onto that mirror, and as we were using the very the final piece of film, the flash of light you get when the celluloid is cut off, became part of the piece.

The second film I made is Blood Orange, shot on a Sunday afternoon in January 2018, in the living room of my former house. It came about through a prism of restlessness combined with boredom and an underlying emotional current, an avalanche that was heading my way which I wasn’t aware of yet at that point. It sat on my hard drive until earlier this year, post-avalanche, when the aforementioned exhibition I had in Amsterdam, with its theme of Transition/Transformation, created the perfect platform for its first outing.

The most recent film I made is Degelen in collaboration with Galya Bisengalieva, shot on my phone, which I spoke about earlier.

The audio piece I did for Amsterdam consists of readings of very brief excerpts of short stories by DH Lawrence, whose writing has had a major impact on me. This work was partly created to make visitors to the exhibition aware of the view onto the bay from the windows where this piece was installed. You can see bits of that view and hear these audio pieces on my Instagram account.

So to cap it all off, the space in which I exhibit becomes a work in itself too, with the same principles of fluke that apply to all my other works.

I realised while putting the new issue of M-A (A SPACE BETWEEN) together that I was also searching for myself within the works collected, which was an extraordinary realisation, can you share any thoughts about searching for answers within your practice?

That gives me enormous pleasure to hear. The last thing I want to do is force my thoughts and feelings onto the viewer, instead I love it when the work functions as a mirror that people can project their own thoughts and feelings onto.

I search all the time, but it isn’t answers that I’m looking for. I want to figure out what it is that I am searching for, which aspects of life I’m trying to explore and why. I don’t think there are any answers in life or art. Life is about openness and exploration - the more you open up to the world and the people around you, the more it enriches you.

With the current wave of self-obsession that came in the wake of social media and a higher level of affluence, people seem to have lost the ability to look outside of their own heads. It doesn’t do anyone any good - the more you navel-gaze the more you end up in a spiral that can lead to mental ill-health. The consumer society we live in thrives on this: the more unhappy we are the more we consume; happy people don’t tend to have this urge to consume. So the big corporations have all to gain from keeping us self-obsessed and miserable, and that counts even more for the tech giants, who need our eyeballs for their data scraping, than the classic, pre-internet corporations.

I’ve gotten to a point now where just looking at, interacting with and being in the world, brings me deep happiness and creates an urge to relay this which is irrepressible. I live in a perpetual state of wonder.

Eva Vermandel, ‘The Sky over the Southbank’, London, 2021. Image courtesy of the artist.

A selection of images by Eva Vermandel are published within issue 3 of M-A (A SPACE BETWEEN).

44. PRADA - A SPACE BETWEEN DESTRUCTION AND CREATION.

A series of artisan artifacts in LONDON.

Hand-stitched fringe dress with metal and crystal embroideries. Spring Summer 2024 Womenswear collection - Prada.

Borrowed utility jackets arrive - worn down, sprouting their internal waddings - modern trophy heirlooms - a life previously lived, the marred surface of belonging. Artisanally aged to costume a chosen reality, a series of identities offer a heroine’s wardrobe of perverse contradictions and intellectual complications.

A series of unlikely pairings flirt, never to be photographed by Lindbergh's lens, alas a delicious melancholia seeps - like Absinthe on flaming cubes of sugar - to be swallowed whole - a sweet liquor rush distilled to delicacy for a grown-up palette.

Canvases shrugged on over hand-stitched flapper fringe - hang by a thread, sway on bleached oak hangers - matte-ly porous and albino against a deeply pigmented patchwork of leathers.

Meticulous micro-metal and crystal-stamped embroideries disrupt a delicacy of textiles - abrupt close-up yet protected with perfected diamond shimmer from afar.

Hand-stitched nylon and leather bag - Spring Summer 2024 Womenswear collection - Prada.

A re-imagined replica of an archival Mario Prada bag tether an assortment of transcience, quietly signaling back to the heartbeat of a brand recognised for its DNA of the luxurious, the rare, and the symbolic.

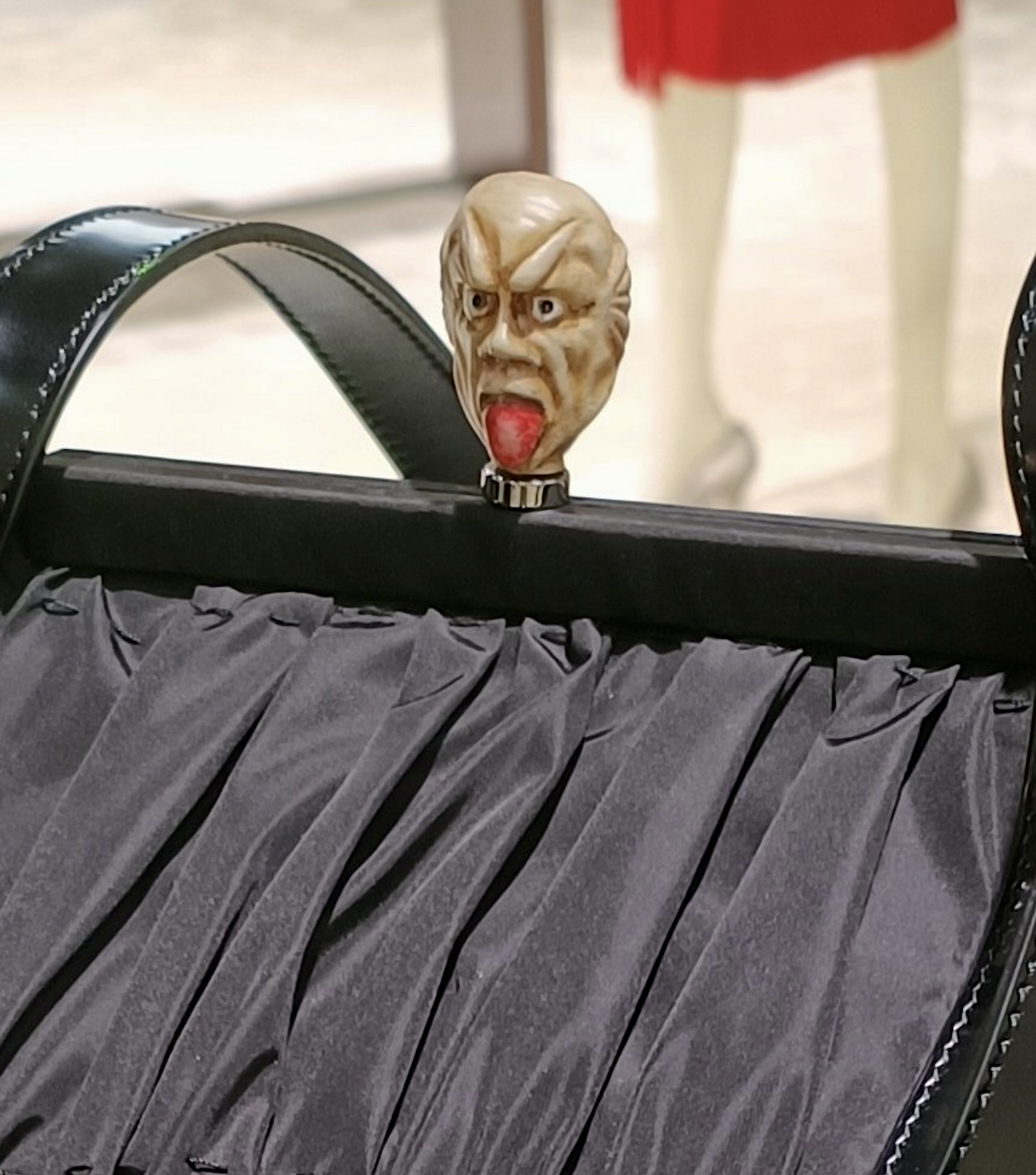

Originally in ruched and pleated black moire, now offered in feather-light, paper-thin nappa or signature nylon - snapping-shut with an ivory lock carved in the form of a satyr head - a direct resin replica of its original mimic the possible Japanese *netsuke origin.

An artifact, more talisman than mere decorative adornment, its protruding tongue and intense grimace remind and reflect back to an ancient - future punk - to destroy is to create.

The Satyr head - a possible netsuke object, originally in the possession of Mario Prada - replicated for a series of bag fastenings within the Spring Summer 2024 Womenswear collection - Prada.

Archival original - image courtesy of Prada X.

*Netsuke, formed by the characters 'ne', meaning root and 'tsuke' meaning attached - are highly prized, hand-carved micro objects originally created as toggle-like fastenings for securing the cord belts worn by gentlemen in 17th century Japan.

The Start Museum 111 Ruining Road, Xuhui District, Shanghai - until January 21, 2024.

Prada Spring Summer 2024 collection is available from January 2024.

Special thanks Rebecca Fletcher-Campbell, Edlira Panxha and Sui Zhonghua - Prada.

43. NACHO GAMMA - A SPACE BETWEEN LIGHT AND SHADOW.

The creative illuminates his personal process.

Nacho Gamma,“Carmine portrait”, London 2020. Image courtesy of the artist.

Framing the Light, was such a memorable performance piece, which came out of an extraordinary time, how do you feel now looking back at that work?

That moment helped me to give an end to a creative and personal block - by keeping myself active and not overthinking it helped me find again my path.

I, very often, return to that room through my memories. It is a way of leaving all kind of pressures behind whilst also bearing in mind the importance of following my instincts.

Nacho Gamma,“Framing the light”, Medium: sunlight, time and graphite, London 13/06/2020. Image courtesy of the artist.

Nacho Gamma, “Framing the light (from 2pm to 10 pm)” Medium: sunlight, time, graphite London 13/06/2020

A sense of light feels so pertinent to your work, from those early iterations using natural light, to the portrait film with Oliver where you painted yourself in white, and then, of course, the symbolism of religious iconography which you return to, can you express why you return to light?

I have the feeling that the passage of time darkens us and that sensation used to worry me, because I had the impression that I was irremediably changing and stopping being myself. Now that I see life through a melancholic shade, I understand that, as it happens with the sunlight which transforms along the day, change is inevitable and looking at things from the darkness lets us see them brighter. That is why, for me, seeing the smallest beam of light has become such a unique event.

In fact, I find the limit between the concepts of light and shadow is something full of mystery that never stops surprising me. ¿How is it possible that two opposite elements need themselves as much to define their own existence?

I also find this duality in the relation between the human and the divine. A question which has not yet been resolved and has been reflected in our history through paintings, texts and monuments made by many other artists.

Nacho Gamma, image courtesy of the artist. From a series first published within issue one of M-A (A SPACE BETWEEN)

Your contribution to the first issue of the magazine was extraordinary, I remember your commitment to that project and the images captured using your Grandfather's camera. The images from the chapel and the boards of visual prayers were incredible to see, please can you introduce that work?

The photos presented in the first issue are the consequence of a transcendental moment for myself.

Fortunately, before moving for a long period to Amsterdam and later to London my grandparents passed away. I mean fortunately because my fear was to experience this situation abroad and not being able to say goodbye to them.

After that, I spent two years abroad, completely distracted about what had happened. But once I finished my Masters and I returned to Spain I decided to go back to their house.

It was a harsh blow to find my grandmother’s chair empty after I opened the door, but it was then when I noticed that I could still grasp their smell still between those walls and I began to cry. It felt like they were still there.

Both their lives were kept in boxes and among all that I found my grandfather’s old camera and some photos taken by him. I immediately knew I had to give it a new life and that moment became a farewell I had never thought I needed until that very same day.

I feel that to define you in terms of media is sort of pointless, you are just so creative, and your contribution to the projects you engage with are so full - I appreciate that there has been an internal tension regarding working as a designer and working as an artist. How do you feel now about this point of view and what have you learned from processing that tension?

As a creative, I like to work in a space between fashion and art, where creating and expressing myself is the only matter. I believe that the set of projects I have been producing create altogether a spectre that fully defines me as a person and a professional.

That is why I despise it when I have to choose between referring to myself as a fashion designer or an artist in order to be understood by others and find a place in this society. When I try to fill the box is when I understand myself the least.

In fact, I do not believe there is any tension between art and fashion, because I believe they are the same, but rather on the relationship between my way of thinking and the constant fear of not being understood, because my work is born from the need of sharing.

Nacho Gamma, “Metamorphosis” presented at the city of Cordoba, at the international flower festival “Flora” Paniculate flower, wire and human body. Cordoba 16/10/21. Image courtesy of the artist.

The performative work you create is incredibly immersive, I always found that to be very impressive – do you find that you need to protect yourself emotionally in the exposure and creation of that work, do you have an alter ego that you engage with when you perform?

I am constantly trying to get to know myself better through my work. It is even a cathartic process I undertake to move on because by expressing my feelings and experiences I avoid any trauma contaminating me.

Performance makes me feel an adrenaline that brings me so much joy and makes me live with much more intensity. While the piece is activated, I feel I have the permission to act without thinking about the consequences.

It is very visceral. It is then when I feel authentic, so this makes me question where the alter ego actually exists, inside or outside the art piece.

Nacho Gamma, “East to west” Medium: snow and red painting for soccer fields. 10/01/2021. Image courtesy of the artist.

Your creative process seems to focus on the sensual, the tender, the body, from the works you have made so far, what do you feel you have learned in terms of your developing point of view?

I do not usually get a pause to reflect on what I have previously made because I am always thinking about what will be next, it is like a thirst that never stops. However now, when I look back, I can see a path that has come to life and I am proud of it.

What I do always bear in mind is that, in order to make something transcendental, it is necessary to stay truthful and consistent with oneself and that there is no better material than time.

Nacho Gamma,“Sunset at Trafalgar” Analógico, Cadiz 3/09/2020. From a series first published within issue one of M-A (A SPACE BETWEEN). Image courtesy of the artist.

42. PHILIP GUSTON - A SPACE BETWEEN THE INTIMATE AND THE ABANDONED.

Philip Guston, Tate Modern - LONDON.

Philip Guston, ‘City’, 1969, Oil paint on canvas. The Guston Foundation.

From the wall of Philip Guston's easel to the infinite landscapes of his subconscious - which duly invite and reject.

Walking from room to room, the effect of retracing Guston is mesmerising - like following footsteps in snow which grow deeper as the man becomes the artist.